White Diamonds

Cruel optimism and the relentlessness of time

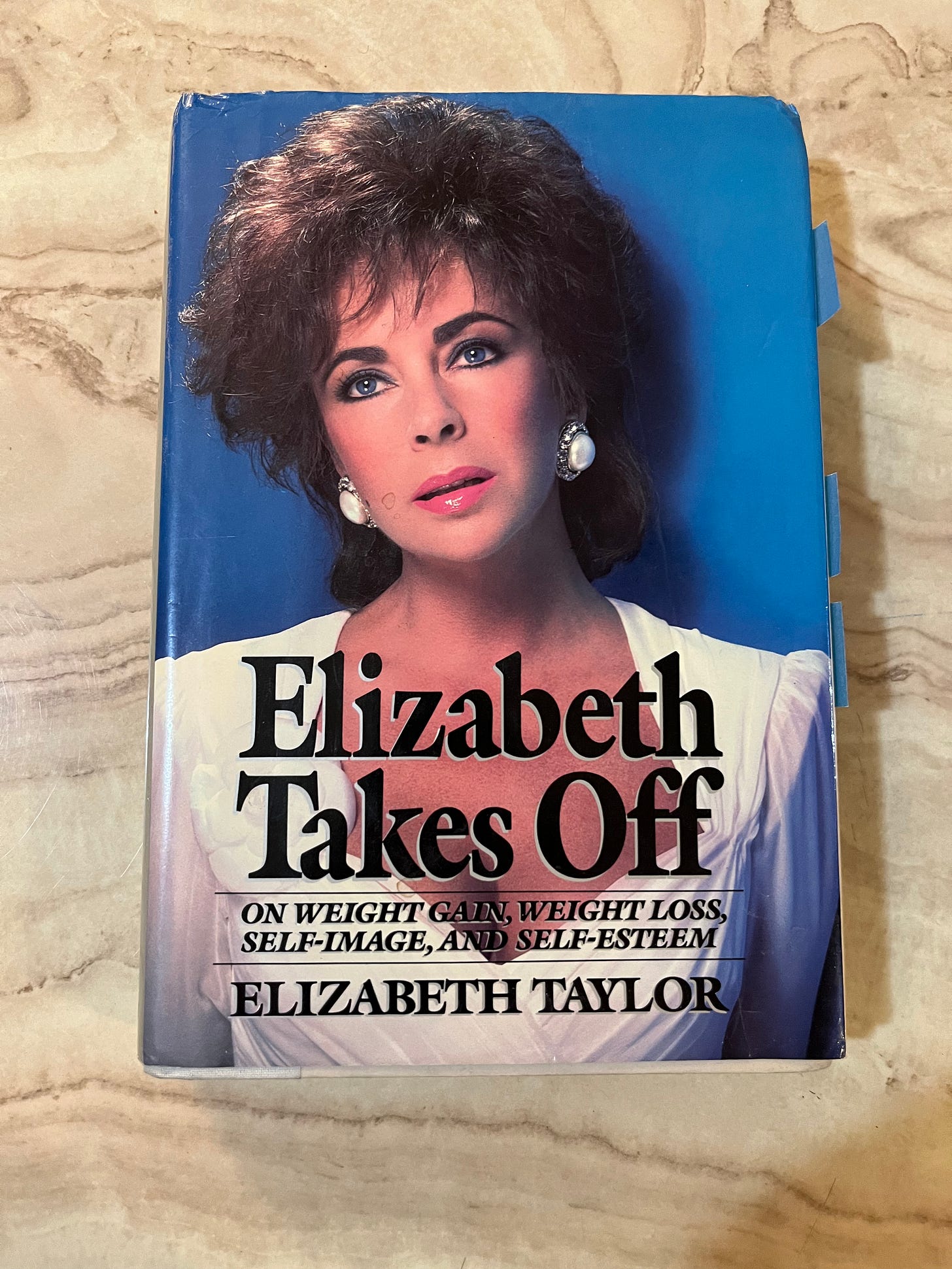

Last year, I read Elizabeth Taylor’s 1987 memoir/cookbook Elizabeth Takes Off and embarked on a project to strictly follow the diet she outlines in the book, documenting and writing about the experience over the course of several weeks. I didn’t really have a particular goal in mind; I described the endeavor as an experiment and I was open to seeing where it would take me and what meaning I could derive from it.

Most people I described the idea to were kind of baffled by it. One day, I met up with some friends in Central Park with my Elizabeth-prescribed dinner in hand (turkey breast, stuffing, and pureed summer squash). It wasn’t what I personally would have chosen to eat for dinner on a 90-ish degree day in mid-June but it was what the text dictated, so it was what I had to eat. “Remind me again why you’re doing this?” my friend Tim asked as I forked little bites of the stuffing I’d spent the last hour making into my mouth. I admit, without an explicit goal I could articulate it seemed like a silly exercise in pointless restriction.

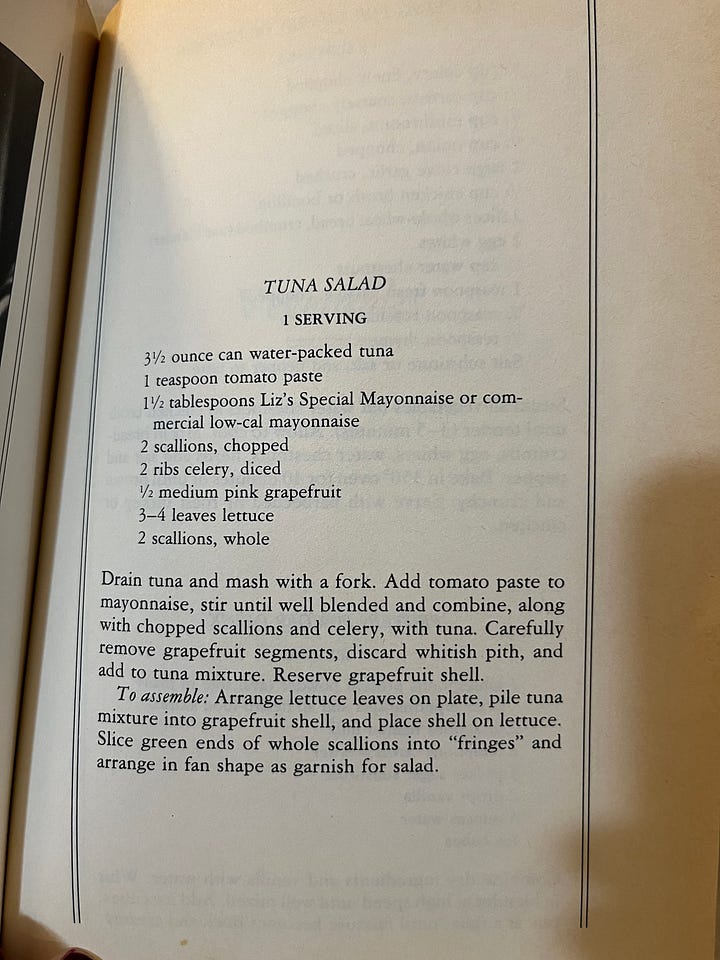

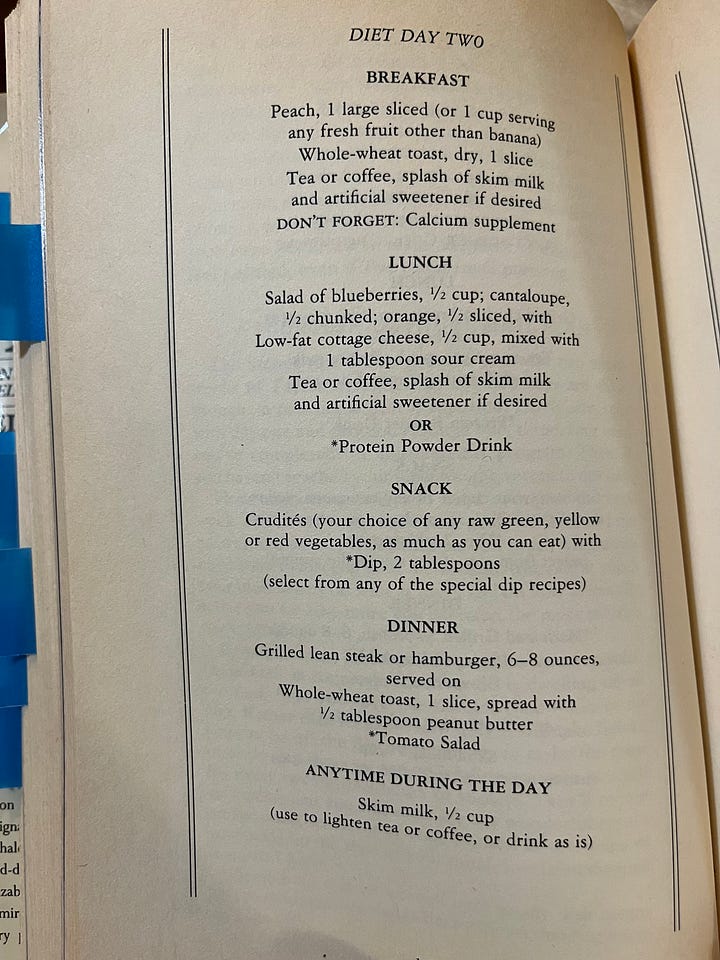

A few people have previously undertaken the Elizabeth Taylor Diet and written about it publicly.1 These essays typically focus on the weirdness of the food—one of Liz’s favorite dinners is a hamburger on toast with peanut butter and her recipe for tuna salad includes bits of grapefruit. For the most part though the recipes seemed fairly normal to me: breakfast is always toast and fruit, lunch is usually some type of salad, dinner is a protein and vegetables. There’s always an afternoon snack of crudites (“as much as you can eat”) with two tablespoons of dip chosen from one of Liz’s many dip and dressing recipes. On the Taylor-Made Diet you eat four times a day. I rarely felt hungry while I was following it.

Something I think about often is what I call the relentlessness of life. You never get a break from yourself or the endless effort you must expend to meet your basic needs. The days keep marching without pause until one day they halt completely. The most accurate artistic portrayal of this conceit that I’ve seen is the late Hungarian filmmaker Béla Tarr’s 2011 masterpiece, The Turin Horse. The film follows a farmer and his daughter over the course of a week while they go about their routine, focusing on the quotidian tasks that must be completed to further their meager existence: fetching water from a well, harnessing the horse to a cart, dressing, eating. Mealtime, consisting of a single boiled potato per person, is the highlight of the day. The film utilizes the long, slow shots that are typical of Tarr’s oeuvre, demanding the audience witness as the repetitive chores are completed in real time.

I first saw The Turin Horse during the Paris Theater’s “Bleak Week,” a week-long celebration of films that showcase the dark side of human existence. Though the film is quite bleak, it also has moments of levity and I sometimes fantasize about rewriting the script to turn it into a comedy, transforming the laborious long shots of the family struggling to complete their daily tasks into moments of slapstick levity. After all, humor works best when it reflects a touch of darkness.

Over the duration of the film, the poor peasant family suffers through a series of misfortunes that unfold like the story of Genesis in reverse. First, the horse refuses to work, then the well runs dry, their world incrementally diminishes until at last even the lamps will not light and father and daughter are left in darkness. At one point, before the final cosmic unravelling, the two try to leave. After packing all their belongings into a cart and coaxing the horse from the barn, the father and daughter slowly move further and further from their homestead, eventually leaving the camera frame, only to turn back and return minutes later. The dominant interpretation of this scene is that there is nothing left beyond their farm, that the outside world has ceased to exist, but perhaps they just thought, “what’s the point?” Why leave when it’s just going to be more of the same wherever you go.

No one tells you being an adult means having to decide what to eat for dinner every single day for the rest of your life. With this project, Elizabeth Taylor told me what to eat for dinner every night, but I still found myself rebelling against her plan: using a different herb because I didn’t want to buy yet another one, replacing sole with swordfish because no grocery store seems to sell sole around here (perhaps sole were so popular in the midcentury everyone gobbled them up and now they’re gone forever), microwaving stuff that’s supposed to be baked or boiled because I didn’t want to turn on the oven. Beyond taking shortcuts, I increasingly found myself questioning the plan: eating stuffing and brown rice as sides in the same meal seems like starch overkill, the recipe for Garlic Cream Dip calls for cream cheese and sour cream, but the recipe Creamy Chive Dip calls for cream cheese and yogurt. The only difference between the two recipes is the presence of garlic in the former, so why use different forms of dairy? Did Liz really think that yogurt or sour cream would impart a significant flavor difference between the two dips? So, even though the dinner thing was theoretically all figured out, it really wasn’t, and there was also all the cooking and washing and buying and fretting about produce going bad that came along with it.

A diet is a kind of cruel optimism—an insincere promise that you’ll achieve a more desirable physical form through sacrifice and that once you achieve that form the other pieces of your life will fall into place. It is a trade between the reliable, spreading pleasure of eating with the pleasure of virtuous restraint. A prescribed diet entails giving up some of one’s sovereignty to an outside authority, ceding one of the few facets of daily life that we reliably have control over. I chose to trust Liz and followed the day by day plan, submitting to her scheme. Though I sometimes questioned her wisdom or found ways to rebel, I committed to staying the course.

Elizabeth Taylor and I are both five foot four. We both have dark hair and eyes of an unusual color (her’s famously a striking violet, mine, gray). We both claim short legs amongst our unfortunate physical flaws. That’s about the extent of the physical similarities between us since Elizabeth Taylor was one of the most beautiful women to ever live and I am admittedly mid.

During the course of my experiment, I tried to find ways to get closer to Liz, to embody her. I wanted to find other ways to hand over my agency to her as I had done with my diet. I watched many of the 50 plus movies she starred in. I drew a beauty mark on my right cheek, mimicking the fabulous mole some Hollywood producer tried to force her to surgically remove early in her career. I considered getting married and divorced several times. I went swimming a few times a week (her preferred form of exercise since a back injury precluded more intense physical activity). I also bought two of her perfumes: Passion, her first fragrance from 1988 and White Diamonds, her 1991 runaway hit that served as a proof of concept for celebrity fragrance. I no longer had to choose what scent I’d wear each day; I would only smell like Elizabeth Taylor.

I admittedly prefer the smell of Passion over White Diamonds, though I enjoy both. Passion is one of those kitchen sink 80s fragrances that has one million notes and would previously be described as “oriental,” but is now classified as a “classical woody amber” by Michael Edwards’s fragrance taxonomy. It opens spicy and herbaceous and dries down to powdery incense and sandalwood with a smidge of something animalic (apparently it was much raunchier when it was first released). It comes in a dark purple bottle and somehow smells dark purple. It would not be out of place in a goth bar or an old timey bordello. Luca Turin gave it one star in The Guide and called it “Z-14 in drag.” I bought a 15 milliliter bottle of it on eBay for five dollars.

White Diamonds needs movement to really shine. If you’re too close it smells a little sour, especially during the opening. It smells incredibly dense on paper, but has a powdery peachiness to it that expands into a white floral bouquet in the air. It’s one of those fragrances where the florals present as a singular mass rather than individual blooms. When I first tried it, I paced back and forth through my apartment with my arms in front of my face, sniffing the blowback radiating towards me. It is designed to waft. Raymond Matts, the evaluator who worked on White Diamonds, assesses perfumes based on how they smell in the air rather than on a blotter, which will hold certain materials for longer than one would experience them diffusing from one’s skin, hence the trailing aura.

White Diamonds is a great perfume. It is great not necessarily because of how it smells—it is a fairly typical classic aldehydic floral. It is great because of its proximity to Elizabeth Taylor and the fantasy it creates by channeling her. It is accompanied by one of the best television advertisements of all time.

My third grade teacher wore a gold orb-shaped pendant around her neck every day. One day the girl who sat next to me in class, Amy, asked her about it. Our teacher opened the orb, revealing two little white tufts dotted with perfume, and told us to smell it. “That’s White Diamonds,” she explained. She left and Amy turned to me and whispered, “those aren’t diamonds, they’re cotton balls.”

Celebrity worship is another kind of cruel optimism—a parasocial proximity to fame that promises, if not transcendence to a realm above an average, unknown existence, then a momentary escape through the fantasy of the life of a star. The kind of life that leads you to believe you’ll have something more interesting to fill your days than concerns with what to make for dinner.

Eventually I fell off the Taylor-Made Diet and went back to my normal, less regimented eating habits. Many of the recipes made it into my regular rotation, as have the two Elizabeth Taylor fragrances I purchased. The only thing I seem to have learned from the experiment is that you can never really get away from yourself.

An example: Cottage Cheese Mixed With Sour Cream? I Tried the Liz Taylor Diet, Rebecca Harrington, 2012. https://www.thecut.com/2012/08/the-liz-taylor-diet.html

Loved reading this one Quinn.

Long Live Liz Taylor ❤️✨